Euran Voyage

The Euran Voyage was an expedition undertaken by the Kaiser Dominus over the course of the years 1642 to 1643. The primary purpose of the expedition was to undertake a state visit to the Free Associative Kingdom of Constancia whilst at the same time to conduct research regarding the flora and fauna of Eura, a continent devastated by the long-term effects of atomic warfare. At the same time the voyage also permitted the Shirerithians to study the trade networks of Passio-Corum on the continent and to establish contacts with the various, unrecognised, lesser statelets of the continent's interior.

Retinue

- Kaiser Dominus Thorgils Tarjeisson Ettlingar Verion

- Order of the Sentinels

- x1 Section of the Blue Company (8 Sentinels)

- x1 Section of the White Company (8 Sentinels)

- Advance Party

- Härold: Zir Spectabilis Dux Titus Lucius Ecthgow (the Silent)

- ZNS Aurangzeb's Revenge

- 2,789 Crew

- 150 Imperial Protocol Officers

- ZNS Aurangzeb's Revenge

- Härold: Zir Spectabilis Dux Titus Lucius Ecthgow (the Silent)

- Main Party

- Chamberlain of the Imperial Household: Zir Serenissima Eliza Ra-Lariat, Matriarch of the Church of Elwynn

- Eye of Cortallia (Imperial Yacht)

- 250 Royal Yachtsmen

- 45 Imperial Protocol Officers

- Warden of the Inner Sanctum: Zir Eques Villelmus Piscis

- 150 Neutered Servitors

- 25 Wards of the Seraglio

- 1 Catamite

- Eye of Cortallia (Imperial Yacht)

- Chamberlain of the Imperial Household: Zir Serenissima Eliza Ra-Lariat, Matriarch of the Church of Elwynn

- Imperial Protection Squadron

- Warden of the Outer Sanctum: Zir Eques Roshan Joan Alinejad

- Þingalið of Tielion Loki: 3,000 housecarls and a fleet of 400 land cruisers under Heorogar Halfdane

- The Fyrd of Metyl Themar: 4,000 thegns under Hrothgar Halfdane

- IRS Medusa

- RAS Kestrel Mk.II x5

- ESB Spiegelflügel-Taube x6

- Trawler/Minesweepers x5

- Tankers x7

- Cargo ships x5

- Warden of the Outer Sanctum: Zir Eques Roshan Joan Alinejad

- Order of the Sentinels

Itinerary

- Izillare the 8th of Vixaslaa, 1642: Arrival off the port of Ithonion of the Shirerithian battleship ZNS Aurangzeb's Revenge - advance party

- Ermure the 10th of Oskaltequ, 1642: Kaiser arrives at Vey International Aiport

- Ermure the 16th of Muulantooqu, 1642: The Shamal blows in - Kaiser Dominus departs for the Molivadisan Theme

- Hyre the 12th of Qinamu, 1642: Resident in Palace of the Governor of Nivardom in Constancia

- Eljere the 23rd of Silnuai to Reire the 3rd of Kuspor, 1643: Visiting the encampment of the Followers of the Sainted Drun, at the Oasis of Drunzhôr, beyond the Dasht-Scôr on the Continent of Eura

- Ermure the 10th of Kuspor to 15th of Kuspor, 1643: Raid on Raspur

- Izillare the 20th of Kuspor, 1643: Negotiations with the Mesazōn of Constancia

- Hyre the 12th Gevraquun, 1643: Notification received of breakthrough in negotiations at the Western Conference

- Eljere the 23rd of Gevrader, 1643: Signing ceremony in Walstadt

Voluntary contributions

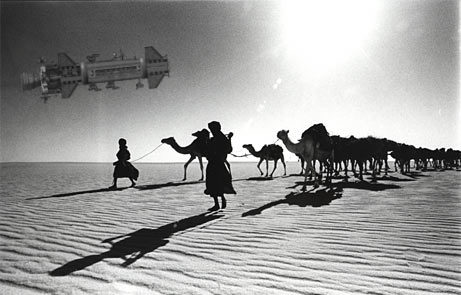

The voluntary contributions of the rulers of Azarkhak, of Raspur, of Nivardom, of the Maritime Free Republic, of the Khalypsil. They had all had been the Kaiser's willing hosts between bouts of negotiation with the Constancians in Vey, and they had all had been willing to pay most handsomely to encourage him to depart. Onwards, ever onwards, to the next wadi, the next oasis, the next town, where the polite, obsequious but insistent whispers had it, for there surely a more recent sighting of the fabled shay' khulūd sandworm had been made.

The Kaiser had eventually gotten wise to this ruse and, between bouts of meaningless, reciprocal and florid complements, larded with the sort of perversely exaggerated praises that would have made even the most jaded harlot flush with shame, the Kaiser would gently intimate that though he was willing – nay eager, ever so eager – to depart once more upon his quest, a lack of the requisite funds constrained him to remain in place. The simple fact of the matter was that to keep his close and immediate retinue of 12,485 followers together in body and soul required a great deal of ready coin, and – mores the pity – banking facilities in the Euran interior were decidedly rudimentary. Abashed by the thought of being a burden – perish the thought – upon his gracious hosts, the Kaiser would offer to send one of the fastest gravships in fleet to the nearest Natopian outpost in Alkhiva, to send a signal back to Shirekeep to arrange for an electronic transfer of funds to be wired across to a suitably trusted moneylender – the ones in Xechaspolis had a good reputation did they not – for collection. The electronic transfer would then be converted into bearer bonds, the bearer bonds into script and the script into bullion, which could then be loaded onto the gravship and returned swiftly hence to defray all the modest items of expenditure that may have been above and beyond the normal obligations of hospitality.

It would be a quick and elegant solution that should not take any appreciable length of time longer than a fortnight to complete. Certainly no longer than a month. At the mention of a month, some of the various potentates less well trained courtiers would bulge their eyes in horror at the prospect of hosting the plague of Benacian locusts and their all consuming lord for another day, let alone another month. Once the look of alarm had passed across the faces of those interlocutors, who had been sat variously on rugs in tents pitched beneath the moonlit skies, between the ochre daubed mud-brick of the laughable native 'palaces' or sat atop the ruins of vast and ancient ziggurats, the Kaiser would know that the moment to make his pitch had come. As the nervous coughs, the strained smiles and the awkwardly averted gazes had subsided, the Kaiser would suggest, apologetically, that if his gracious hosts would be minded to become partners in his expedition, and to make a contribution towards its success, they would be handsomely rewarded from the bottomless treasury of the Imperial Republic.

It must be said that not every Khan, Satrap or Nabob grasped the extraordinary opportunity. Some even took offence, having misunderstood the invitation to join a partnership as a crude attempt at extortion. So it was, tragically, that Raspur burned for the second time in its history. It's Khan, having been advised of his misapprehension, readily apologised for the untoward incident and became one of Kaiser's most generous and munificent contributors.

For those who agreed to become partners, all that was required was a generous contribution of whatever portable wealth they had to hand, gold and silver, diamonds, rubies, jewellery of antique quality, antiquities of any kind. Enough to be of assistance to the Kaiser's provisioners once they reached the next settlement. In return they would receive a letter of credit, authenticated by the Kaiser's great seal, entitling them to a full refund of the contribution plus an ex gratia payment of 25 percent on top of the assessed value of the original contribution. Of course, it would be an appreciable while before the Count of the Sacred Bounty would be able to dispatch an emissary to disburse repayment on behalf of a grateful Imperial Republic but, in this manner, the Kaiser could be gone from his present locale as soon as the agreed contribution, assessed by the Chamberlain and the Grand Imperial Neutered Servitor, had been made. Typically the Kaiser would be solvent once more and on his way within the week.

Sadly the Kaiser never did get to see a sandworm in the majesty of its natural environment. Although he did have a few paintings that suggested otherwise commissioned in anticipation of his triumphal return to Shirekeep. More happily it transpired that his household had routinely over-estimated the cost of provisioning, leaving him in a treasure hoard of gold, silver and emeralds of a total value conservatively estimated at 251 million Erb.